By MARK GAMIN

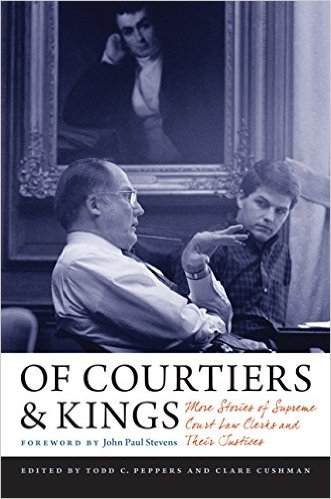

Review of Of Courtiers and Kings: More Stories of Supreme Court Law Clerks, edited by Todd C. Peppers and Clare Cushman

Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015

The New Yorker magazine was a hallowed institution to many, with a unique tone, culture, and talent roster, including Robert Benchley, Dorothy Parker, Harold Ross, and umpteen other oddball geniuses. The goings-on in its Manhattan offices, the recluses in the corner, the James Thurber drawings penciled onto the plaster walls – all these have made for a number of published behind-the-scenes accounts over the years, so many that even the most ardent fan may be forgiven for wondering, when encountering yet another New Yorker book, “again”?

So it is, as well, with law clerks in the Supreme Court of the United States, about whom there is, apparently, no end of books.

A 2006 book, Courtiers of the Marble Palace: The Rise and Influence of the Supreme Court Law Clerk, was a seemingly exhaustive research project and history of law clerks in the United States Supreme Court. Nevertheless, author Todd C. Peppers announced, in his preface to that book, "I am not ready to end my pursuit of the elusive law clerk." He wasn’t kidding.

He followed that book by editing (with Artemus Ward) a volume of essays and reminiscences on the same subject, In Chambers: Stories of Supreme Court Law Clerks and Their Justices (2012). Artemus Ward had previously (in 2006) written his own book, "Sorcerers’ Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court." Now Professor Peppers (this time with co-editor Clare Cushman, Director of Publications of the Supreme Court Historical Society) returns with a sequel, Of Courtiers and Kings: More Stories of Supreme Court Law Clerks and Their Justices.

The fecundity of the subject – the subject being a bunch of really smart lawyers, right out of law school, who serve as assistants to Supreme Court justices for a year or two – is surprising. Or, rather, it would have been surprising, not so many years ago (the law clerk institution itself is around 100 years old; the modern version of the institution probably half that), before the advent of law clerk studies, symposia, law review articles (bunches of them), whodunit novels (John Grisham) and satiric novels (Christopher Buckley), not to mention a couple of short-lived television shows.

Of Courtiers and Kings comes in three parts. Part I, “The Early Days of the Clerkship Institution,” runs from the last years of the nineteenth century to the 1930s. Part II, “The Rise of Clerks,” ends around the first part of the Earl Warren court in the 1960’s; and Part III, “Modern Clerks,” presents recollections of clerks for such later justices as Abe Fortas, John Paul Stevens, Sandra Day O’Connor, David Souter, and others of that approximate vintage. This is not to say that the book is a complete history of these years or the justices that served then; it is not. It is a grab-bag, rather, much as the earlier In Chambers was a grab-bag, of (one senses) whatever written pieces the editors could obtain at the time, and then arranged chronologically for publication. Nothing wrong with that.

Most of the book consists of essays written by former law clerks, mostly in festschrift-style, with nary a discouraging word. Thus “an extraordinarily wonderful person to be with and work with” is the description given Justice George Sutherland, who served on the Court from 1922 to 1938, by one of his clerks (he only had a total of four during his tenure – a period before the now-standard one- or two-year clerkship terms). Harold Burton, former mayor of Cleveland, Ohio and Supreme Court justice from 1945 to 1958, was “an outstanding example of humanity at its best – fair, honest, loyal, reasonable, generous, and courageous.” A Tom Clark (1949 – 1967) clerk calls him “the sweetest and most thoughtful man I have ever known”; an Earl Warren clerk (Chief Justice from 1953 to 1969) says he was “the only really great man I have ever known.”

Not all the prosaic memories consist of mere gushing. Some, such as that written by Louis B. Cohen (a 1967 clerk), are strange, lovely, perfect:

I once described Justice [John Marshall] Harlan as the man I would send to Mars to show the Martians what human beings could be like. I don’t know what percentage of clerks would say that they would not trade their clerkships for anything else in their professional lives, but I’m in that group.

Cohen’s daughter clerked for the Supreme Court, too – John Paul Stevens. The penultimate chapter of Of Courtiers includes tag-team reminiscences from a few of these parent/sibling clerkships; Amanda Cohen Leiter’s is the best. She writes, touchingly, that if she needed a human exemplar to send to Mars, “I would pick my dad.”

Take that, Justice Stevens.

This worshipful tone is to be expected: most law clerks, devoted to their justices, remember their tenure like Louis B. Cohen does – as a highlight of their careers, perhaps even one of the best years of their lives. (For an unlucky few, such as those who clerked for William O. Douglas or James McReynolds, both, according to the clerk accounts, bully-martinets, it can be one of the worst.) So it is unsurprising that most clerks, looking back, idealize their judicial bosses. The epigram “No man is a hero to his valet” has no application here, and festschrift is not intended for revealing your idol’s tics or weirdnesses.

Nevertheless, some good stories make it through the encomiastic firewall; and some of the portraits are more than two-dimensional. One can’t help but empathize with such a character as Potter Stewart – the genuine humanity of the guy – when one learns, via his 1972- and 1973-term clerks, that he hated Warren Burger (his Chief Justice), was frightened of William Rehnquist, and had the habit of chewing the ends of his neckties.

And it tells you something about Rehnquist to read the story of him and his 1974 clerk, going to play ping-pong in an upstairs room, next to the Supreme Court gym. As they were entering the room, a janitor walked out, leaving the place reeking of marijuana. But Rehnquist never reported the matter, so the janitor kept his job. Someone should have told Potter Stewart that he really had nothing to fear from the old softie.

Of Courtiers and Kings is fun in the way that an insider’s account of an institution such as The New Yorker magazine can be fun. But, really, is there anything more there? Peppers says, in this book, that he has been researching the subject of Supreme Court law clerks for fifteen years; Artemus Ward spent ten years on his 2006 book. Given all the attention paid to law clerks in recent years, it is surely legitimate to ask whether there is sufficient ore left in this particular historical vein to justify the mining.

Take the first chapter of Of Courtiers, titled “The ‘Lost’ Clerks of the White Court Era.” “White” is Edward D. White, who was confirmed as associate justice in 1894 (he voted with the Court in the 1896 separate-but-equal case, Plessy v. Ferguson) and served as chief justice from 1910 until his death in 1921. “Lost” means, apparently, that little was known about them about until now, which is understandable because they were not, really, “clerks,” at all – not in the sense we think of law clerks today, and have thought about them for some fifty years. They were (mostly) stenographers, often attending law school at night. The author of this chapter, Clare Cushman, clearly went to some lengths to, as she says, “rescue these clerks from obscurity” – but why? God bless them all, but their historical importance or interest is negligible; for these men obscurity is not any particular shame, for the reader no especial loss.

Even for the later clerks – those who clerked, say, for the “Four Horsemen” who blocked Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal reforms in the 1930’s (George Sutherland, Pierce Butler, James McReynolds, and Willis Van Deventer) -- the biographical information provided only occasionally rises above the trivial. The reader learns, for example, who the clerks married, and whether they later became members of the American Judicature Society or the Order of the Elks (really), and suchlike things. As to their role in or knowledge of the dramatic events of that era – the fights over Roosevelt’s National Industrial Relief Act and other legislation, and his court-packing plan, and the “switch in time that saved nine” of West Coast Hotel v. Parrish – there is little or nothing.

The notion that Supreme Court law clerks might be worth attention, even scholarly attention (as opposed to being merely anonymous and harmless drudges) appears to have arisen, in the first instance and way back when, as the result of a 1957 news magazine essay by a callow William Rehnquist. Rehnquist was then fresh off his own clerkship with Justice Robert Jackson (during which, as it happens, he authored a memorandum that appeared to find favor with Plessy v. Ferguson; he had some explaining to do about it, years later, during his confirmation hearings to be Chief Justice). Today the piece seems tepid, but Rehnquist was saying that a left-wing bias on the part of a majority of Supreme Court clerks was operating in favor of a certain class of petitions for certiorari. These clerks, he said, favored (consciously or unconsciously) expansion of federal power, extreme solicitude for criminal defendants, and governmental regulation of business – “in short, the political philosophy now espoused by the Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren.”

From that seed in U.S. News & World Report sprouted a fascination, not to say obsession, with the supposed power of Supreme Court clerks that has always seemed far-fetched – of a piece with most any other conspiracy theory. The notion that Supreme Court justices – mature and experienced lawyers, expert not only in the law but in politics (as they must be to get to the Court in the first place), and life-tenured to boot – could be swayed against their will or better judgment, by twenty-somethings who are going to be around, in any event, for a year or two at most, is simply not very believable and never has been.

Yet the idea of the law clerk as Wormtongue (or, as Rehnquist had it, Rasputin) persists. (The clerkship studies boom is also helped by something of a breach, in recent years, in the general rule of confidentiality that had, heretofore, been observed by most clerks scrupulously.) It has been the basis for a good deal of speculation in the media, not to mention some quasi-scientific studies in the law reviews that appear to come up short on analytic rigor. In any event, and as Peppers points out, the evidence from the clerks’ writings in Of Courtiers does not support the theory of undue influence. Much of it is to the contrary, such as the 1964-65 Stewart clerk who wrote to his fiancé: “I am steadily becoming indoctrinated and noticing a tendency on the part of all clerks including me and my co-clerk to think like the office, which is actually okay.”

The book’s final chapter, by Laura Krugman Ray, concerns not so much whether clerks have too much influence over their justices, but the more intriguing question of how justices influence their clerks when the clerks themselves, years later, are named to the Court. There are three of those today: Chief Justice John Roberts (who clerked for then-Associate Justice Rehnquist), Stephen Breyer (Arthur Goldberg), and Elena Kagan (Thurgood Marshall). As Ray shows, Goldberg claimed to write the first decision expressing doubts, as a general matter, about capital punishment – and he used what he called “the worldwide trend toward abolition” as argumentative ammo. Breyer has an obvious attraction for the use of foreign law (evidenced in a number of opinions, and in his book The Court and the World, published last year) as well as an antipathy for the death penalty (see last term’s dissent in Glossip v. Gloss). Did – or does – one justice’s predilection follow the other’s?

The book could have used some cull-editing. Most every clerk feels the need to write an explanation of the “cert pool,” whereby the thousands of petitions for certiorari (the Court’s discretionary jurisdiction) are divided among most (not all) of the justices’ clerks, as a time-saving device or, given the large numbers of cases and briefs, and the complexity of the legal issues, a matter of survival. If the cert pool discussion was limited to one explanation by one clerk, the book would be twenty pages shorter, and that would be a good thing.

That and a few other nits notwithstanding, Of Courtiers and Kings is a fine addition to the clerkship literature for those who haven’t yet fallen out of love with the sound of law clerks talking about themselves. So what’s next? Endowed chairs in Law Clerk Studies? The Harvard Journal of Legal Clerkiana? Such things might be the culmination of a tendency to view clerks and, for that matter, the Court itself, in a way that is neither justified nor intellectually healthy. (“The lionizing of contemporary law clerks,” as a John Roberts clerk is quoted saying, “can make them forget they are serving the institution.”) The tendency is already evident, indeed, in the book’s title. Those people in the black robes? They’re not “kings,” not royalty – they’re just (as Article III of the Constitution says) judges.

And their assistants, the “courtiers”? For Pete’s sake – they’re just law clerks.

Posted on 22 February 2016

MARK GAMIN, a Cleveland lawyer, is a former law clerk for the U.S. Court of Appeals.