By STEVEN LUBET

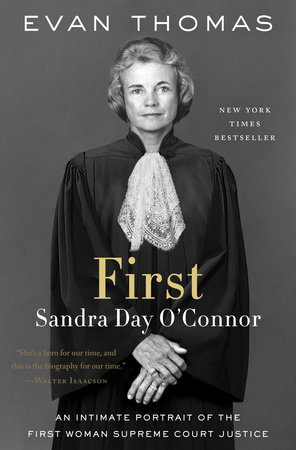

Review of The Chief: The Life and Turbulent Times of Chief Justice John Roberts, by Joan Biskupic, and First: Sandra Day O’Connor, by Evan Thomas

New York: Basic Books, 2019

New York: Random House, 2019

The challenge in a judicial biography is to make the material interesting to general readers as well as to lawyers and academics. That is not always easy, as even an important Supreme Court justice may have led a relatively unremarkable life. This essay reviews Joan Biskupic’s biography of John Roberts and Evan Thomas’s biography of Sandra Day O’Connor, both of which are well-written and exhaustive. It will come as little surprise that Justice O’Connor is a far more interesting subject than Chief Justice Roberts, and that difference is also reflected in their jurisprudence. Roberts, whose career arc was steadily and predictably upward from high school to the Supreme Court, affects a technocratic, nearly antiseptic, judging style. O’Connor, in contrast, led a more complex and eventful life. Her experiences brought her to an empathetic, less detached, approach to her work, taking fuller account of the impact her decisions could have on individuals.

Joan Biskupic specializes in Supreme Court justices, having previously written biographies of Antonin Scalia (2010), an earlier one of Sandra Day O’Connor (2006), and Sonia Sotomayor (2015). Scalia was an outsized personality and both O’Connor and Sotomayor overcame unprecedented obstacles. They would have been fascinating subjects even if they had never served on the Court. But what is there to say about Roberts other than that he is chief justice?

Biskupic’s task is made even more difficult because Roberts is still sitting, and so his papers are unavailable. He spoke with her only off the record, and everyone else with useful information—clerks, colleagues, and friends—was understandably circumspect in how much they would disclose. Biskupic makes a valiant effort to say something revealing nonetheless, though Roberts has not given her much to work with. His pre-SCOTUS life is basically a tale of scholastic achievement, followed by career successes, all by dint of overwhelming brainpower and prodigiously hard work. It is impressive but, to be honest, pretty dull.

As the gifted son in an affluent home, Roberts was given nearly all of life’s advantages, and he took full advantage of them. Raised in Long Beach, Indiana, a wealthy enclave on the shore of Lake Michigan, Roberts attended an exclusive boarding school, where he succeeded at everything he tried. And he knew why he was doing it. One of Biskupic’s great finds is Roberts’s handwritten application letter to La Lumiere School (reproduced at 12). “I won’t be content to get a good job by getting a good education,” he wrote, “I want to get the best job by getting the best education.”

If all happy families are alike, at least in terms of literary interest, so are all outstanding students. Roberts marched through Harvard College and Harvard Law School, and went on to clerk from Judge Henry Friendly of the Second Circuit, and then Justice William Rehnquist of the Supreme Court. In 1981, a recommendation from Rehnquist got Roberts a position in the newly installed Reagan administration, as a special assistant to Attorney General William French Smith. He was 26 years old.

Roberts’s outstanding work drew the attention of White House counsel Fred Fielding, who recruited Roberts to his staff in 1982. After only a year at DOJ, Roberts was on the “fast track,” which was how his former colleague Kenneth Starr put it in a congratulatory note (82).

One thing kept leading to another, as Roberts’s brilliant career continued to advance in the Reagan and Bush 41 administrations, by virtue of his exceptional intellect, impressive work ethic, and dedication to staunchly conservative principles. In 1993, following the election of Bill Clinton, Roberts returned to private practice at Hogan & Hartson (now Hogan Lovells), where he would establish himself as one of the outstanding appellate litigators of his generation. He argued 39 cases before the Supreme Court, winning 25.

After two stalled nominations to the District of Columbia Circuit (in 1992 and 2001), Roberts was finally confirmed by a Republican controlled Senate in 2003, marking the penultimate step in his quest for the “best job.”

When Sandra Day O’Connor resigned in July 2005, Roberts was nominated to take her seat on the Supreme Court. Before the Senate could hold confirmation hearings, however, William Rehnquist died, and Roberts was re-designated as Bush 43’s nominee for chief justice. Roberts was confirmed on September 29, 2005 (by a vote of 78-22), just in time to take the center seat when the Court convened in October.

At last, things got interesting, mostly because the stakes got higher and far more visible. As chief justice, Roberts, steadily moved the court to the right. Justice Anthony Kennedy, who became the new “median justice,” allowed the new majority to issue a series of 5-4 decisions advancing long-standing conservative objectives on campaign finance, school desegregation, voting rights, gun ownership, contraception, union dues, and President Trump’s “travel ban,” among others.

Kennedy’s swing vote resulted in a few liberal outcomes (notably on same-sex marriage), but Roberts defected from the conservative position only when it came to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which he famously voted to uphold in NFIB v. Sebelius.

Biskupic has done great reporting on this issue, which is the most fascinating vignette in her book. She details the positions taken by each justice at the Court’s sacrosanct conference, as well as Roberts’s initial vote to overturn the individual mandate (222). In the course of the next month, however, Roberts negotiated with Justices Kennedy and Ginsburg, in the hope of reaching an accommodation that would save at least part of the ACA. Kennedy rebuffed him, but Ginsburg, to paraphrase Tammany Hall’s G.W. Plunkett, saw an opportunity and she took it. "I was forcing myself to stay awake and work on the opinion," she told Biskupic (242). As everyone knows, Roberts joined the liberals and conservatives howled as the ACA lived to face other challenges.

The greatest undertaking for biographer is to give us not only the “what,” but also the “why.” Here Biskupic falls short, although with no lack of effort. Even after the blow-by-blow, we are left wondering why Roberts departed from his conservative colleagues in the ACA case. “Viewed only through a judicial lens,” writes Biskupic, “his moves were not consistent, and his legal arguments were not entirely coherent.” And so,

Perhaps Roberts' move was born of a concern for the business of health care. Perhaps he had worries about his own legitimacy and legacy, intertwined with concerns about the legitimacy and legacy of the court. Perhaps his change of heart really arose from a sudden new understanding of congressional taxing power (248).

There seems to be no good answer. Biskupic calls her own subject an “enigma” (346).

On the other hand, Roberts’s views have been completely consistent on issues of race and racial preferences. He is a hardcore advocate of the so-called color-blind Constitution, and therefore dead set against ever taking race into account in legislation or judicial decisions. He has voted against affirmative action in higher education, racial balance in public schools, and the crucial “preclearance” provision of the Voting Rights Act. He tends to speak in banalities, writing once that “it is a sordid business, this divvying us up by race” (178). In another opinion, striking down Seattle’s school desegregation plan because it involved racial balancing, he insisted, against all experience, that “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race” (10). As with many highly accomplished, affluent white people, Roberts’s head start in life is invisible to him.

According to Biskupic, who conducted hours of off-the-record interviews with Roberts, he has believed, at least since college, that “too much attention was being put on the numbers of racial minorities in classes and in hiring” (253). That was easy to say for someone who had grown up in an all-white enclave attending all-white schools. Even so, Roberts denied that “his own background and personal experiences” had any influence on his decision making (267). He insisted that he was just calling balls and strikes, which Biskupic calls a “veneer of neutrality” (267). Perhaps the best we can say is that he is opposed to racial remedies because he has always been opposed to racial remedies. Or, as Biskupic put it, “it is hard to know when or how it happened, but his views became entrenched” (253).

In that regard, O’Connor was virtually the anti-Roberts. Her views—on race and other contentious subjects—were far from entrenched. Flexibility and close attention to the discrete facts of each case earned her the role of “swing justice”—a sobriquet she disliked—on a sharply divided court. Many of O‘Connor’s pragmatic positions were traceable to her life experiences, which were as distinctive as Roberts’s were bland. It is no fault of Biskupic’s that The Chief lacks any sense of dramatic development; she did the best she could with the material at hand. Her own biography of Justice O’Connor is far more interesting, and Evan Thomas—with the benefit of sources unavailable to Biskupic in 2006—takes the subject to yet another level.

If John Roberts’s “fast track” to “the best job” took him almost ineluctably to the U.S. Supreme Court, while maintaining a cool demeanor that can blunt even the best attempt at biography, Sandra Day O’Connor followed a far more winding road, even an adventurous one, as detailed in Evan Thomas’s absorbing First: Sandra Day O’Connor. She did not go from law school to prestigious clerkships, and then to an insider’s position in the White House. In fact, she was unable even to get interviews with top California law firms, although she had graduated at the top of her class at Stanford. One Los Angeles firm did let her in the door, but only to offer her a secretarial position, explaining that “our clients won’t stand [for] being represented by a woman” (43).

Before she was nominated by President Ronald Reagan in 1981, O’Connor had been an unsalaried assistant district attorney in California, a civilian lawyer in the U.S. Army’s Quartermaster Corps in Germany, and then a stay-at-home mom and a storefront lawyer in Phoenix. Her true professional ascent only began when, at age 39, she was appointed to a vacancy in the Arizona state senate. Within a few terms, she became the first woman majority leader in any U.S. legislature, followed by stints as a state trial court judge and appellate court justice.

O’Connor’s childhood and youth demanded independence and resourcefulness, preparing her well for later detours and disappointments. She was born on her parents’ cattle ranch—the 160,000 acre Lazy B, in an arid corner of southeast Arizona—in a house that had neither electricity nor indoor plumbing. Because there were no schools within reasonable distance of the Lazy B, six-year old Sandra Day was sent to El Paso, where she lived with her maternal grandmother while attending a private elementary school. She returned to the ranch for summers, and then as an adolescent, where she rode horses and joined in calf branding (and castrating) under the stern, and sometimes unforgiving, supervision of her father.

Always a precocious student, Sandra Day entered Stanford in 1946, at age 16, having skipped two grades. She was one of only a few women in her class. Graduating in only three years, she entered Stanford law school when she was 19 years old.

In law school, Sandra Day was surrounded by WWII veterans, one of whom was William Rehnquist. For many years it was reported that the two law students had casually dated, and Rehnquist told his clerks only that they had “gone to the movies” once or twice (219). Thomas reveals that there was more to it. Their dating had been serious, with Rehnquist proclaiming his love during their third year at Stanford. “I know I can never be happy without you,” he told her. “To be specific, Sandy, will you marry me this summer” (42).

Rehnquist’s was the third marriage proposal Sandra Day received while at Stanford. She accepted the fourth one, from John O’Conner, a fellow law review editor in the class behind her. They would be married for 57 years.

Thomas is able to include such intimate details because Justice Connor and her family gave him unprecedented access to her personal and professional papers. In addition to her official papers, archived at the Library of Congress but closed to the public, Thomas also obtained a trove of letters and notes dating back to O’Connor’s college years. Both Sandra and John O’Connor kept diaries of her years on the court, and John also wrote an unpublished and never previously seen memoir. With encouragement from the family, Thomas was able to conduct on-the-record interviews with seven SCOTUS justices, 94 former clerks (of 108), and scores of O’Connor’s friends and relatives, including college and law school classmates, Arizona neighbors, and many participants in the O’Connors’ active social life. Even treating physicians—for Sandra’s breast cancer and John’s Alzheimer’s disease—sat for interviews.

Unlike Roberts, O’Connor’s life story provides meaningful insights into the origins of her judicial views. Having experienced gender discrimination first-hand, and having learned how to function and succeed in a previously all-male world—cattle ranch, legislature, and bench—she was well situated to mediate conflicting views on the most troublesome issues before the Supreme Court.

In 1992, after Clarence Thomas had replaced Thurgood Marshall on the Court, abortion rights seemed to be hanging by a thread. And when the Court heard argument in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, a challenge to Pennsylvania’s restrictive abortion law, the writing seemed to be on the wall. As explained in First, Chief Justice Rehnquist initially “counted five votes to reverse Roe and assigned himself the Court’s opinion” (279). Before Rehnquist’s draft could circulate, however, Justices Kennedy, Souter, and O’Connor coalesced around a compromise. The result was a joint opinion upholding many of the statute’s restrictions while reaffirming “the essential holding” of Roe v. Wade. According to Evan Thomas, it was O’Connor who persuaded Kennedy to sign on by “appealing to his basic sense of decency and fairness.” It was also O’Connor who contributed the crucial “nuts-and-bolts” in the joint opinion, establishing the “undue burden” test that has survived, if barely, to this day (280).

If Joan Biskupic is politely (and appropriately) skeptical of Roberts’s labored insistence that his background does not influence his judgments, Evan Thomas is quite certain that O’Connor’s life experience—as a woman and a mother—informed her decision to salvage Roe from outright reversal. In an interview, one of her former clerks observed that “the justice understood what was at stake for women...She had experienced childbirth. She understood the challenge of carrying a child to term [and] fully appreciated what women can face in these deeply personal decisions” (263).

So it was in the affirmative action cases. O’Connor disliked “victimhood and identity politics,” but, as another former clerk explained, “she had a lot of experience of her own to know that the playing field was not always level” (347). Thus, in Grutter v. Bollinger she cast the deciding vote to uphold the affirmative action plan at the University of Michigan Law School, noting that its “holistic” approach to racial preference served to admit a “critical mass of underrepresented minority students” whose very presence would undermine “racial stereotypes” (350).

Not every O’Connor compromise was liberal. In Bush v. Gore, she voted with the conservative majority to install George W. Bush in the White House, on the questionable rationale that continuing the Florida recount would violate the Equal Protection Clause. Thomas reveals that O’Connor persuaded Scalia to accept her theory, even though he privately ridiculed it as “a piece of shit” (332). O’Connor also contributed perhaps the most notorious passage in the unsigned opinion, making Bush the only beneficiary of its reasoning. The holding of the case, she wrote, was “limited to the present circumstances, for the problem of equal protection in election processes generally presents many complexities” (332).

It is impossible to say whether Roberts or O’Connor will be remembered as the better or more influential justice, and not only because Roberts, after 14 years, is still in mid-career. Judicial reputations rise and fall with political currents and historical trends, and the replacement of Justice Kennedy by Justice Kavanaugh has only recently made Roberts the median justice as well as the chief.

But whatever the ultimate assessment there is no doubt that O’Connor has led the more fascinating life, which leads me to one last observation. Perhaps SCOTUS justices can be divided into two broad groups: the Path-Takers and the Way-Makers.

John Roberts is the ultimate Path-Taker, following a determined trajectory of political appointments, serving mostly as a functionary or operative (in the non-pejorative sense) for powerful sponsors. Other recent Path-Takers are Justices Brett Kavanaugh, Neil Gorsuch, Elena Kagan, and Stephen Breyer. Way-Makers, on the other hand, have had to overcome tougher beginnings and serious obstacles, with no clear track to follow. In addition to O’Connor, recent Way-Makers include Justices Clarence Thomas, Sonya Sotomayor, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. This division does not tell us much about the quality of the justices—there are better and worse jurists in both groups, depending on one’s metric—but it speaks volumes about the challenges facing their biographers.

Posted on 7 October 2019

STEVEN LUBET is Williams Memorial Professor at the Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law. His most recent book is Interrogating Ethnography: Why Evidence Matters (Oxford, 2017).