By DIANA MUIR APPELBAUM

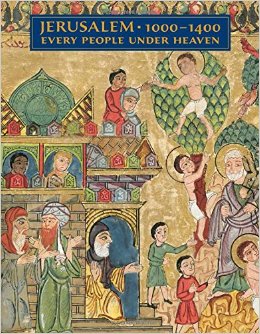

Review of exhibit Jerusalem 1000 - 1400: Every People under Heaven (Sept. 26, 2016 through Jan. 8, 2017)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

“Beginning in about the year 1000, Jerusalem captivated the world’s attention as never before. Why did it hold that focus for the next four centuries?” Certainly nothing in the exhibition’s entry vestibule – where this question is written on the wall – offers a clue. Soft-focus images of Jerusalem projected onto the walls show a grayish city under a dull sky, with a pall of smog hanging over the buildings. The gold-covered Dome of the Rock looks as though someone flipped the finish from “shiny” to “matte.”

Unfortunately, the curators have taken a similar approach, presenting a soft-focus version of medieval Jerusalem as a city shared equally by Muslims, Christians and Jews, with the differences among them no more significant than the choice of whether to make falafel with fava beans or chickpeas. Imposing such a narrative requires a major elision of reality.

In one display case, a copy of a history of the First Crusade by William of Tyre is opened to show images of the coronation of Queen Melisende and her consort Fulk in Jerusalem. It is paired with a handsomely illuminated Quran. One of a number of magnificent Qurans on exhibit, it conveys the idea that the Quran, like the Bible, contains material about Jerusalem. The Quran, however, never mentions Jerusalem.

Early Christians fought a pitched intellectual battle about whether to regard the Hebrew Bible as the word of God. The decision to revere both Old and New Testaments meant that the history of Jerusalem before the birth of Christ became part of Christianity. Add to this the fact that key episodes in the life of Christ and the Acts of the Apostles take place in Jerusalem, and the centrality of the crucifixion and resurrection, and it is no wonder that the Christian imagination focused on Jerusalem.

Islam is very different. The Bible is not a Muslim holy book and Jerusalem is not described by the Quran as the site of any of the events in Muhammad’s life. What does exist in Muslim tradition is the legend of Muhammad’s Night Journey, an event described in the Quran as his journey on horseback in a single night from Mecca to “the furthest mosque” (al-masjid al-aqsa,) and from that mosque to heaven. Although the Quran does not identify the location of the furthest mosque and scholarly opinion varies, Muslim tradition identifies it with Jerusalem. Moreover, while there were Jewish and Christian kingdoms ruled from Jerusalem, the city has never been the capital of a Muslim kingdom or state.

The curators have my sympathy. Given that Jewish objects related to Jerusalem in these centuries consist largely of manuscripts, and recognizing the advantages of displaying at least a sample of the enormous number of splendidly illustrated medieval Christian books about Jerusalem, the curators needed to find a type of Muslim text that appears not to exist.

The most interesting Muslim manuscript on display with a connection to Jerusalem is a pilgrimage certificate with folk art illumination testifying that a man named Sayyid Yusuf bin Sayyid Shahab al-Din Mwara al-Nahri went as a pilgrim to Mecca, Medina, Karbala, Hebron and Jerusalem. There is also an alcove filled with illuminations of the Path of Paradise of al-Sara’I made for Abu Sa'id Mirza in 1466 that includes a delightful image of Muhammad astride his flying horse. Beautiful as they are, it is hard to say why they are included in an exhibition about medieval Jerusalem.

While the major failing of this exhibit is that the curators have built it around a false premise, it suffers also from a lack of focus apparent in the inclusion of many objects with little or no relationship to the city.

The first room showcases a glistening gold necklace - perhaps a head filet – exquisitely crafted of fine filigree and tiny granulation. This masterpiece of the goldsmith’s art is matched in the final room by an even more dazzling gold object: a reliquary from Limoges. They make dramatic bookends for a sprawling and somewhat inchoate exhibit.

The necklace was part of a hoard of jewelry buried not in Jerusalem, but in Caesarea, on Israel’s Mediterranean coast, by someone who did not survive to return for it. The large reliquary, elaborately covered with jewels, carvings, and enameling, was made in Limoges, France. It was not owned in Jerusalem, does not depict Jerusalem, and is related to the city only by Christian allegory in which Jerusalem represents not only the Church, but the ideal world that will be ushered in by the Second Coming.

A curator, recognizing that the relationship of the Limoges reliquary to Jerusalem is tenuous, has provided an object label that is a minor masterpiece of convoluted justification. We are told that the reliquary belongs in this exhibition because, “although French in origin… (it) is firmly linked to the Eastern Mediterranean (by) turquoise-colored faience, a type of ceramic associated with the region.”

A inlaid brass box, round, domed, and made for a Muslim in Syria or Egypt, as magnificent in its way as the reliquary, has similarly little relationship to Jerusalem, although the label provides a hypothetical linkage to the city involving the idea that all domes in Islam reference the Dome of the Rock.

To be clear, this exhibition is studded with remarkable things. There is a 10th-century prayer mat from Tiberias, woven from straw of exquisite fineness. It gives some idea of the type of prayer mats that may have been in use in Jerusalem. The magnificent manuscripts on display could constitute a major, stand-alone exhibition. Among the more striking illustrations are those in the golden Psalter of Queen Melisende of Jerusalem (c. 1135) and the Norman Cloisters Apocalypse (c. 1330.) There are column capitals from Nazareth, intended for a church, that had not yet been installed on the day in 1187 when Saladin crashed into town. Buried under the rubble of the artist’s workshop, their delicately carved detail has experienced no weathering; they will radically and permanently change the way you see Romanesque sculpture.

Much of the time, however, the exhibit is so detached from Jerusalem as to make me wonder whether the curators, experts in medieval art, had ever visited Jerusalem or studied these faith traditions. Without some explanation of the sort, it is hard to understand the statement on a wall devoted to The Dome of the Rock and the Al Aqsa Mosque, that “At the southwest corner of the great esplanade that overlooks Jerusalem stands the Dome of the Rock.” The southwest corner is, of course, the location of Al Aqsa; the Dome of the Rock is at the center of the enormous platform. This may be an easily corrected mistake; what comes next is more problematic, because it reveals the ease with which a well-intentioned effort to produce a politically acceptable exhibition can lead instead to the distortion of fact.

In large letters, the text on the wall explains that the Dome enshrines a natural stone outcropping “variously understood as the site of Abraham’s sacrifice, the location of the tabernacle in the Temple of Solomon, and the point of departure for the Prophet Muhammad’s Ascent to Paradise.”

“Abraham’s sacrifice” is an odd phrase, not in common use in English where the traditional phrase is “the binding of Isaac.” It appears to have been chosen to elide the distinctiveness of these faith traditions.

In the Jewish and Christian Bibles, Abraham was prepared to sacrifice Isaac, and Jews and Christians traditionally identify the location as the stone at the center of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Islam has a similar story, but the name of the son is not given in the Quran; in Muslim tradition Abraham is usually said to have been about to sacrifice Ishmael, and the location was the black stone in Mecca known as the kaaba.

The exhibit’s litany of “Abraham’s sacrifice, the location of the tabernacle in the Temple of Solomon, and the point of departure for the Prophet Muhammad’s Ascent to Paradise” is problematic in an additional way, because one of these things is not like the others, one of these things just doesn’t belong.

Muhammad’s ascension to Heaven and Abraham’s near sacrifice of his beloved son are legendary accounts. The location of the ancient Temple, by contrast, is an archaeological and historical fact. The curator responsible for the text may have attempted to stay just inside the bounds of accuracy by referencing the “Temple of Solomon.” The construction of a temple on this spot by a king named Solomon—as opposed to the later Temple built on the site by the exiles returning from Babylon—cannot be proven, which gives the text the uncomfortable appearance of what Stephen Colbert calls “truthiness”—a very different thing from truth.

The great puzzle of this exhibition is why someone would assemble this grand procession of manuscripts, textiles, glass, pottery, carvings, metalwork and drawings and make no effort at all to answer the question posed at the entrance: Why did (Jerusalem) hold the world’s focus for the next four centuries? Or even attempt to give viewers a sense of what Jerusalem was like in those centuries. It is almost tempting to believe that these scholarly medievalists are unaware of the options made possible by the invention of photography.

A graceful Crusader baptismal font with Norman column capitols survives on the Temple platform. Known as the Dome of the Ascension, it is revered as the starting point of the Prophet’s visit to Heaven. I am not suggesting that it should have been disassembled and shipped to the Met to give viewers a sense of what the city was once like. A photo would have done the job.

The delicately inlaid minbar of Nur al-Din, the lofty interior of St. Anne’s Church, the Crusader arches at the Al Aqsa Mosque are a few of the structures from this period that still stand, structures that would have conveyed some sense of the medieval city. It is even possible to evoke a time and place, for example, by taking advantage of the renowned acoustics of St. Anne’s Church to record Gregorian chant, and play it softly near those striking column capitols from Nazareth.

The coda to the exhibit, of course, is a dedicated gift shop, itself an unintentional parody of the exhibition’s rather loose definition of “Jerusalem.” It features Turkish kilim, Persian textiles, and tourist-grade metal trays from Turkey, glass beads from Nepal, and exotic Middle Eastern spice blends from New Bedford, Massachusetts. The closest it comes to Jerusalem is a display of olive oil from “Canaan, Palestine.”

As it stands, Jerusalem 1000 – 1400: Every People under Heaven is a procession of remarkable objects in search of a narrative. Given that even today Jerusalem continues to captivate much of the world’s attention, that is a pity.

Posted on 3 October 2016

DIANA MUIR APPELBAUM is the author of Reflections in Bullough's Pond: Economy and Ecosystem in New England. She is at work on a book tentatively entitled Nationhood: The Foundation of Democracy.