By JOHN HAVARD

Review of Island on Fire: The Revolt That Ended Slavery in the British Empire, by Tom Zoellner

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020

On April 15, 1831, the man who had replaced William Wilberforce as head of the abolitionists in Parliament addressed the House of Commons. Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton called for nothing less than slavery’s “extinction.” The whole slave population of Britain’s West Indian colonies, Buxton lamented, were in “a miserable condition” and the whole system was “so destructive of their moral and physical welfare” that it ought, in his eyes, to be abolished. But in a repetition of a familiar pattern, this advance in anti-slavery argumentation was not followed by action on the ground.

Buxton pointed to examples of “oppression” and “cruelty.” But he did so, he hastened to add, “without the slightest feeling of hostility” towards the white plantation owners who generated their wealth and status from Caribbean slavery “and without the slightest disposition to cast reproach upon them.” Buxton backed away from the growing public mobilization in favor of emancipation, denying that the case for ending slavery depended on “popular feeling.” He grounded his arguments in moderate entreaties and broadly palatable assertions. That included sympathy for the slaveowners, who were caught against their will, he claimed, in a system they had not chosen—and who could not extricate themselves from the use of slave labor without ruining their personal finances.

Abolition was in the doldrums. Britain had banned the slave trade in 1807. But calls to abolish slavery outright—and to free the enslaved—had languished. Abolitionists in Parliament were stymied. As for the enslaved persons themselves, they were, Buxton told Parliament, depressed. He pointed to the appalling mortality rate in Britain’s West Indian colonies—statistics whose cold, hard truths would play a key role in reframing debate (at a time when planters simply decried claims about pervasive cruelty as fake news). The opponents of abolition, meanwhile, claimed that the enslaved were restive and ripe for discontent, riled up by calls for emancipation. Whether they favored gradual amelioration or preservation of the status quo, both sides agreed that keeping the enslaved in check would be crucial to prevent West Indian society from becoming unviable.

Tom Zoellner tells another story. Island on Fire (winner of the 2020 National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction) concerns itself only glancingly with parliamentary debate in Westminster. Its focus falls on Jamaica, Britain’s largest sugar colony and the home to hundreds of thousands of enslaved West Indians. The book reconstructs the channels of print culture and evangelical religion that linked the Caribbean with abolitionist debate in Britain—and the circuits of communication that enslaved and formerly enslaved people across the Americas established among themselves. At its core is the charismatic deacon Samuel Sharpe and the so-called Christmas Day (or Baptist) rebellion, which set the island ablaze in the final weeks of 1831.

As was the case with the late eighteenth-century movement to end the slave trade, fervent emotion played a crucial role in galvanizing political energies. Buxton had sought to hold popular feeling at arm’s length from parliamentary debate. At a certain point, the momentum became unstoppable. But in Zoellner’s telling, developments in Jamaica (later the same year that Buxton spoke in the Commons) played the pivotal role in making emancipation a reality. That began with nonviolent resistance. But peaceful work stoppages gave way to a violent revolt—and brutal reprisals. Island of Fire reconstructs these weeks of turmoil and their aftermath in compelling detail, from the smell of smoke on the sticky night air to the retributory violence that left flagstones slick with blood.

Enslaved people in the Caribbean enjoyed small mercies. The Christmas Junkanoo festival involved clapping along with a traditional figure wearing ox horns. But eighteenth-century Jamaica was, in many respects, an utterly wretched place. Zoellner follows Trevor Burnard and Vincent Brown in capturing a putrid atmosphere of disease and early demise, coupled (among whites) with a kind of manic, hollow-eyed debauchery. Death, as Brown has argued, was a great leveler. The mortality rate for whites was one in five. The far-larger enslaved population faced still more horrifying rates of mortality, together with state-sanctioned violence. But the enslaved could at least claim strength in numbers.

They could also discern changes in the political weather. Despite efforts to restrict literacy (and to block access to more subversive Bible passages) news and rumors abounded. “It became common for enslaved people to carry torn scraps of British newspapers,” Zoellner notes, which were used by some as “wrapping for the cherished tickets that would allow them to leave the plantation for Sunday services”—a “material metaphor for the blending of the message of Christianity” with a “newfound awareness of a bigger political world” (80).

The enslaved pastor Samuel Sharpe was highly educated: a notable public speaker and devoted reader of the Bible, with an encyclopedic knowledge of the island from his preaching. His reading of religious texts intermingled with his reading of current affairs back in England. In sermons, he mixed the overseas news with censored passages of scripture, using the “imprimatur of the church” to give his message authority. “When fused with rumors of abolitionist sentiment and sugar boycotts back in Britain,” the combination was “electric” (81).

Zoellner marvels at the speed of the social networks that spread news of what came to be known as “the business.” Those “verbal webs of underground communication”—as was the case for New York’s sizeable Black population during the eighteenth century—included “higglers at the market, trusted negotiators, sympathetic free colored people, and traveling Baptist deacons like Sharpe” (84–5). The December rebellion “almost started by accident.” In the days leading up to Christmas, fellow laborers refused to whip an enslaved woman, “brandishing their machetes” and threatening to throw the plantation owner into a vat of boiling sugar. The story, Zoellner notes, “went viral,” sending the message that enslaved people might make a stand of solidarity “flashing through the invisible network of information” (107).

Those same channels made room for misinformation, including imagined conspiracies. The paranoia and perpetual watchfulness of the planters helped place the island on a semi-military footing, adding permanent surveillance to the ritualized brutalities that sustained a “vast agricultural prison camp” (7). But fears about resistance and talk of possible uprisings were accordingly dismissed as just “another Jamaican rumor, part of the tissue of myth and half-truths” that undergirded a tyrannical police state (108). Slaves were attributed with malign, seditious intent—and seen as a lurking threat. The inability to see beyond these stereotypes left whites unable to discern the traces of rebellion once they were actually in motion.

Sharpe chose fellow conspirators who, like him, belonged to a “slave elite,” building a sophisticated “cellular structure” (83). An inquiry later marveled “that many of the chief conspirators and ringleaders were to be found among those enslaved people who, from their situations as head-people or confidential servants were the least worked, were the best clothed, and received the most indulgence.” “A reader can almost hear the bafflement,” Zoellner writes, “in a similar way that modern Western governments have been surprised by revolutionaries or terrorists who come not from the poorest quarters of society but the layers of the educated bourgeoisie” (83).

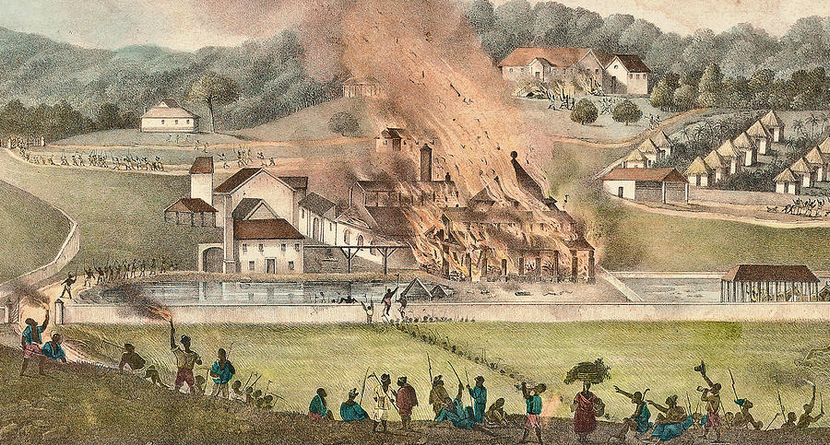

While the extent of Sharpe’s militancy remains opaque, he and his followers proved to be surprisingly professional fighters. When British soldiers sailed into the harbor, they “quickly became ensnared in a guerilla war they were ill prepared to fight” (3). At the core were the fires: five weeks of burning, looting, and crop destruction. The rebellion, whatever Sharpe’s intentions, took on a life of its own. Two hundred Jamaican estates were damaged or destroyed. At least five hundred enslaved people died in battle or (regardless of their demonstrated culpability) faced bloody reprisals, by way of court-martials, on-the-spot executions, and “outright human hunting” (4). British rulers were forced to go back to England to answer for the embarrassment. But in one sense, the enslaved had taken their cues from Parliament.

Reports had circulated that MPs were debating whether and how to grant the enslaved their freedom. That was indeed the case. But Sharpe, who had read the thorough coverage of the parliamentary debates, willfully read them in more fulsome terms. (“I know we are free,” he insisted, “I have read it in the English papers” [88]). As had also been the case in Demerara in 1823, rumors that slaves were to be emancipated fueled anger at a conspiracy to deprive them of their freedom. While imaginary in the narrow sense, that conspiracy did, of course, capture the overall reality. “The idea of freedom had so intoxicated their minds as to nullify all I said,” one Baptist missionary observed, echoing claims that slaves had been rendered excitable by talk of emancipation (109). In fact, the whispers of parliamentary legislation simply gave oxygen to an already kindling fire.

Island on Fire is saturated with fascinating detail, with fresh attention to primary texts and familiar episodes. A chapter on the history of sugar moves from its caviar-like status for the first Queen Elizabeth to images of an entire nation growing plump on sweet tea and British baking displays as the enslaved toiled. The claim that Britons were addicted to sugar, while illuminating and carefully substantiated, may risk undermining the larger picture. (I am probably addicted to my iPhone. So what?) Island on Fire makes the realities of slavery in Jamaica vivid and real: from the “languid afternoons” that planters spent “drinking rum-and-lime punch on the veranda” while watching their “human property chopping rows of sleek sugarcane” (8), to the martial law and unlicensed violence that culminated with the heads of the enslaved on poles. Zoellner captures the complexity of a slave society that featured myriad social distinctions, spiritual practices, and relationships to power—and shows how, despite the odds, enslaved people took the matter of freedom into their own hands.

Those in Jamaica may have caught wind of how the tide was turning against slavery in Britain. But Zoellner’s book has the laudable aim of recovering the agency of the enslaved and the imprint that they made upon metropolitan debate. The mark made by their actions was, Zoellner claims, a large one. This was, the book’s subtitle proclaims, “the revolt that ended slavery in the British Empire.” But should we really give the events of December 1831 so much prominence in the halting story of abolition? Is it really plausible to claim that the Jamaica revolt “broke the back” of pro-slavery support in Britain, paving the way for the freeing of the enslaved?

The answer to those questions is: yes. Accounts of abolition focused on politics in England have attributed slave resistance and public sentiment with crucial importance in securing the passage of emancipation. Island on Fire makes the force behind those demands palpable, mounting a compelling case that the 1831 revolt played the critical role in turning abolitionist demands into reality. The groundwork for emancipation was already in place: anti-slavery sentiment, working-class agitation, questions about long-term viability (although Zoellner joins with those challenging the premise that slavery was no longer profitable). But we need only look to Buxton’s speech, earlier the same year as the Jamaica revolt, to see that this was not enough. Calls to improve the condition of slaves through colonial legislatures, first made almost a decade earlier, had been spurned. For Buxton, appeasing slaveholders’ consciences and tempering demands for change had offered a faltering path forwards. Matters looked different when white plantation owners were running for their lives.

Following the revolt, efforts were made to scapegoat missionaries. Planters sailed to London, in what became a last-ditch effort to defend the institution. At a public meeting, one prominent plantation owner made an emotive plea. Running a slave operation was the only way a man could survive in Jamaica, he maintained. Besides, the British people “had effectively forced their island cousins to do it,” Zoellner summarizes, “in the name of mercantile power and cheap sugar” (210). All those pretty, pastel-colored cakes were laced with blood. As for the enslaved, he painted a dire picture of the consequences if they were allowed to be free. But popular opposition to slavery was already mounting. The events in Jamaica served as a further jolt to the elite, at a time when change was already in the air.

The passage of emancipation came on the heels of dramatic constitutional upheaval. The 1832 Reform Act expanded the franchise and dramatically reimagined England’s electoral map. The elimination of so-called “rotten boroughs” undermined the influence of the West India interest, who could no longer purchase seats in Parliament. While “middle-class” in some respects, these reforms marked the convergence—if not the culmination—of decades-long radical grassroots organizing and working-class participation. Abolition had its own added appeal, foregrounding humanitarian sympathies, in the service of a virtuous and noble endeavor. We may see the coming of emancipation, in this climate, as all-but-inevitable: a further victory for Britain’s early nineteenth-century “Age of Reform.”

But that would be a mistake. Abolition generated fervent support in its own right. Petitions were signed by hundreds of thousands, driven in many cases by female reformers. (Wilberforce, for his part, told these women to stay in their lane; he and others were content to let more radical demands for immediate abolition fall by the wayside). At the level of local organizing, anti-slavery energies converged with agitation around the Reform Act. Working-class people, signing petitions in favor of reform and petitions supporting emancipation in quick succession, saw the causes as related (even as some activists indulged ludicrous claims about the supposedly pampered life of slaves). But at the level of parliamentary debate, those speaking on these issues talked past one another, passing like ships in the night.

Violent protest, Island on Fire shows, played a key role in breaking the deadlock. But Zoellner does not elide the realities behind the struggle, nor blind us to what else might have been. The 1790s had seen the founding of the republic of Haiti, offering a model for revolutionary transformation. But far from ushering in radical new horizons, ending slavey in the British Empire became, in some respects, convenient. Compensation was offered, but to wealthy slave owners. Abolition helped inspire further demands for political change, including within England. But appeals to the plight of the enslaved also gave way to invidious comparisons with factory workers, who would soon rally under another label: the white working class.

Sharpe did not harbor ambitions of founding an independent republic. The prospect that white Jamaicans might secede—and seek to join the United States—was a source of bloodcurdling fear among the enslaved. They knew what America meant. Sharpe would, given his demonstrated interest in international affairs, have known about Haiti. He had planned only to have his followers resist working if they were not declared free at Christmas: a general strike. But the movement he helped unleash became “the spark that ignited the movement to end British slavery less than two and a half years later and an invigorating example for abolitionists who then turned their attention to the overthrow of slavery in the United States” (5).

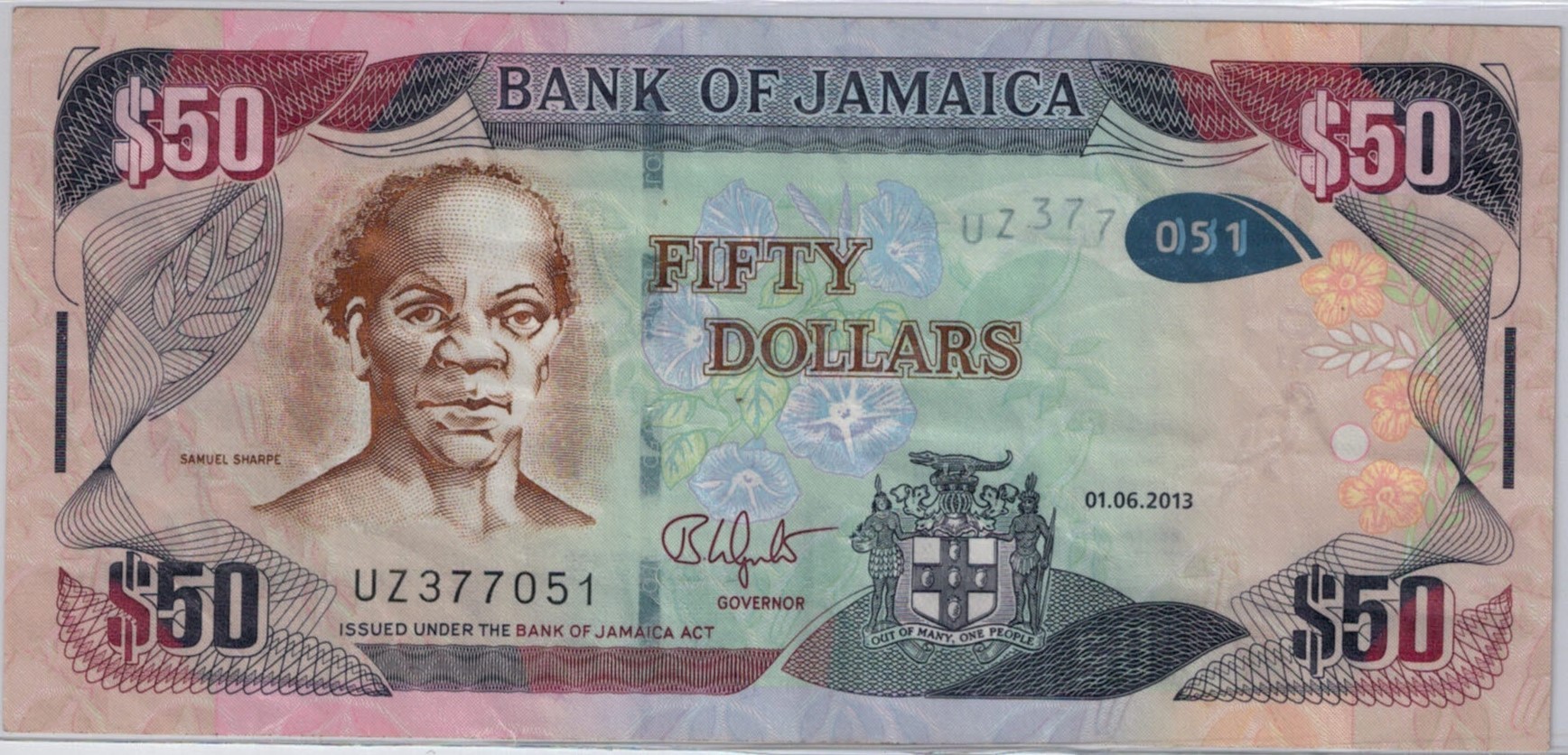

“In their previous rhetoric,” Zoellner observes, “abolitionists had largely cast slaves as objects of pity without voices of their own or the ability to change their own fates” (85). Even enlightened discussions tend to treat the colonies as a mere appendage, making the enslaved marginal to the story of their own emancipation. Island on Fire turns those accounts on their heads, advancing the forceful case that Sharpe’s rebellion, “with one forceful punch in the name of liberty, hastened the cause of abolition by several years, if not decades” (5). The book ends, suitably enough, in contemporary Jamaica, where Sharpe’s face graces the fifty-dollar bill and ritual bonfires commemorate his rebellion. Sharpe has been neglected, an oversight this compelling book amply corrects. But on the island, his story still burns bright.

Posted on 2 October 2021

JOHN HAVARD is Associate Professor of English at SUNY Binghamton. He is author of Disaffected Parties: Political Estrangement and the Making of English Literature, 1760-1830 (Oxford, 2019).