By CORINNA BARRETT LAIN

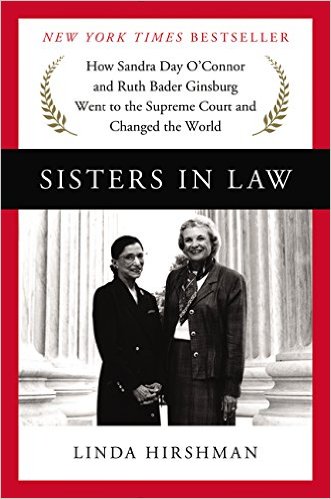

Review of Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O'Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World, by Linda Hirshman

New York: Harper Collins, 2015

Last week, my husband had the misfortune to tell me that he liked the shoes I was wearing. I told him that was sexist. I had just finished Linda Hirshman’s new book, Sisters in Law, and have been on high alert for gendered roles, expectations, and apparently even compliments, ever since. That’s what a good book does—it puts the reader in the writer’s headspace even after putting it down. Sisters in Law is a good book.

Like most good books, Sisters in Law has a number of strengths and also a few weaknesses. In this review, I briefly reflect on both, then turn to what struck me most about the book, the thing I’m still thinking about and struggling with: what it means to be an elite. The good, the bad, and the ugly (truth)—here is my reaction to Sisters in Law.

First, the good—what I loved about the book. The aim of Sisters in Law, aptly captured in its subtitle, is to tell the story of “How Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World.”[1] The book does that, and more.

For example, the reader gets a bird’s eye view of the petty indignities each of these women endured early in her career. Seared in my memory is the story of how a young Ruth Bader Ginsburg, then clerking for a district court judge, was in the backseat of her judge’s car while he was giving a ride to a court of appeals judge who worked in the same building, the renowned Learned Hand. Ginsburg asked Hand a question and he answered, as if talking to the windshield from the front passenger seat, “Young lady, I’m not looking at you.”[2] I can still feel the sting, the humiliation she must have felt.

The reader also gets an inside look at the sexism on the Supreme Court when Ginsburg was arguing her cases and later, when Sandra Day O’Connor arrived. “Women are not fungible with men (thank god!)” wrote Lewis Powell in a note about one of the cases Ginsburg had argued.[3] From William Brennan’s refusal to hire Ginsburg as a clerk because she was female, to Warren Burger’s longstanding practice of assigning O’Connor the Court’s opinion in less important cases, to Harry Blackmun’s imitations of O’Connor’s speaking style and belittling response to Ginsburg’s comments on an opinion that she should have been assigned to write—the boys on the bench made clear that these sisters in law would never truly be one of The Brethren.[4]

Two unexpected bonuses briefly deserve mention. First, the reader gets a fantastic sense of how social movements infiltrate the law at the micro level. We know that social movements find expression in the law, but there are few accounts of how exactly that happens—how lawyers who care more about the cause than the case meticulously manage the litigation so as to bring incremental change that adds up to a shift in the legal landscape, and how hard that is to do when most anyone can ask the Supreme Court for review, and one is operating under the very conditions of disempowerment that the litigation is trying to change. Ginsburg’s clever and graceful responses to these challenges alone makes Sisters in Law a worthwhile read.

Second, Sisters in Law is a nice reminder of the dialogic relationship between law and the society it regulates. Most “court and culture” scholarship focuses on how culture impacts the law.[5] Sisters in Law illustrates how law impacts culture as well—sometimes for the good, sometimes for the bad—and how that impact can in turn feed back into the law. Hirshman captures the point beautifully in describing O’Connor’s approach to abortion cases during her tenure: “She would never provide the crucial fifth vote to send women back to 1972. But she would not let them move beyond the backlash that erupted after 1973 either.”[6] The women’s movement of the 1970s changed the law in fits and starts, with its most ambitious efforts triggering backlash and setbacks that threatened to erode the success of the movement itself. Sisters in Law allows us to see this phenomenon unfolding on the front lines.

All this Sisters in Law accomplishes while engaging and entertaining the reader with Hirshman’s charming style. Section headings like “Even Liberal Lawyers are Conservative,”[7] “Women’s Lib at the Liberties Union,”[8] “Abortion Battles in the Culture Wars,”[9] and my personal favorite, “WWTFWOTSCD (What Would the First Woman on the Supreme Court Do?)”[10] give a glimpse of the treat in store for those who read Sisters in Law. The book is a great read.

But it could have been even better, and that brings me to what I didn’t love about Sisters in Law. First, I didn’t love the organization of the book. I experienced it as jumping from Ginsburg to O’Connor and back in seemingly random order, sometimes within the same chapter and without subheadings to signal the move. And I kept wanting to connect the two biographies; I wanted to know what O’Connor was doing while Ginsburg was doing this or that, and vice versa. Did Ginsburg ever argue a case before O’Connor?, I wondered as I was reading. The answer is no—Ginsburg’s last case before the Supreme Court was in 1978, and O’Connor didn’t become a Justice until 1981—but I couldn’t answer that question after reading the book; I had to look it up.[11] A little more attention to structure and the connections a reader will naturally want to make in a joint biography would have gone a long way.

Second, and more pointedly, the book could have used another edit before going to press. The first time I saw the word “delicious” used to describe something other than food, I thought it was richly descriptive.[12] By the third time, I thought it was overdone, and by the fifth time, I thought it was trite.[13] There were also a few typos. I don’t know whether O’Connor’s first clerk was Ruth McGregor or MacGregor, but the two spellings of her last name end one sentence and begin the next—they are literally back to back—so someone should have caught that.[14] And then there is the reference to Plessy v. Ferguson, described as an “1877 decision”[15] when in fact it was decided in 1896.[16]

All this is to say that in my mind, Sisters in Law wasn’t quite ready when it went to print. It’s a good book, but I would be less than candid if I did not admit to being a tad disappointed in the execution of this marvelous project. I wanted Sisters in Law to dazzle me and it didn’t, although at times it shines brightly. (As an example of just how brightly it shines, I find myself wondering whether the publisher was sexist—didn’t Sisters in Law deserve the same meticulous review and spit-shine polish that other books published by Harper Collins get? And am I sexist for wanting more, as a woman, from a book about such important women? I’d like to think that I would have been equally sensitive to these sorts of glitches in any book, but one can never know.) In the end, Sisters in Law did not meet its enormous potential, but it was still a great read with valuable insights in abundance—and that’s no small accomplishment.

That said, what struck me most about Sisters in Law was not its highs or lows, but rather what it showed about what it means to be an elite. I thought I knew. Dahlia Lithwick captures my pre-Sisters in Law thinking nicely in her essay entitled, “Yale, Harvard, Yale, Harvard, Yale, Harvard, Harvard, Harvard, Columbia: The Thing that Scares Me Most About the Supreme Court.”[17] As Lithwick puts the point, “[E]lite schools beget elite judicial clerkships beget elite federal judgeships. Rinse, repeat.”[18] Fancy education, little to no real world experience, and upper-class values—that’s what I thought it meant to be an elite, at least when considering the composition of the Supreme Court.

Now I know better. The understanding I had wasn’t so much inaccurate as it was incomplete, and what I was missing may well be the most important part. Consider, for example, the story of O’Connor’s rise. Her volunteer work for the Republican Party (a luxury that came with having a husband who brought home a lawyer’s pay) helped her create the political connections that landed her a seat in the Arizona Senate, and later, on the Arizona Court of Appeals. Her and her husband’s social connections with similarly situated movers and shakers on the Arizona political scene resulted in an invitation to an excursion with mutual friends of Warren Burger, who O’Connor met on the trip. That connection, in turn, gave rise to Burger inviting O’Connor to be a part of a delegation of judges attending a legal conference in London, which further cemented their professional relationship. Later, when Ronald Reagan was looking to make good on his promise to appoint a female to the Supreme Court, both Burger and William Rehnquist, O’Connor’s longtime friend from Stanford, touted her name. She bonded with Reagan over talk about horses and was confirmed 99-0, despite never having presided over a federal case.

Ginsburg had a different path, but she, too, understood the power of harnessing her place in the social stratosphere to make it work for her. On more than one occasion, Sisters in Law tells of Ginsburg deftly reminding those with whom she was dealing of some connection they had as elites before moving to the subject of whatever it was she wanted.[19] “Just us natural elites here,” Hirshman writes of this classic Ginsburg move.[20]

The point is this: O’Connor and Ginsburg were outsiders as women, but there were insiders as elites, and that made a world of difference. Both success stories attest to the raw talent, exceptional intellect, and abiding resilience that each of these women had—yet both are also a testament to the importance of being a social elite, someone who knows people who know people and can forge relationships with those in power as part of the ruling class. The old adage, it’s not just what you know, but who, has scarcely been more true. High caliber made each appointment possible, but what made it happen was clout.

None of this is particularly earth-shattering, but the subtler side of being an elite—those uber-important connections that don’t appear on paper—is something I haven’t thought much about and haven’t seen much discussed in the public discourse over the Justices’ elite status. Sisters in Law was an eye-opener in that regard. Having read the book, I have a newfound appreciation for what it means to be an elite, and it has been on my mind ever since.

Part of what I’ve been thinking about is a question. O’Connor and Ginsburg were very different kinds of elites. Which appointment to the Supreme Court did more for the women’s movement? Yes, the movement needed both. But which appointment made the bigger inroad—O’Connor in 1981 or Ginsburg in 1993?

Consider O’Connor. As Hirshman rightly recognizes, “she was the perfect First.”[21] O’Connor’s views were not a threat to the establishment, and that was an enormous part of what made her appointable in 1981. But it also limited what she would do on the bench. In case after frustrating case, Sisters in Law reminds us of O’Connor’s vote against women on issues such as sex discrimination, sexual harassment, Title IX, and abortion (it was O’Connor who advocated the undue burden test, and then said everything except spousal notification requirements passed).[22] “O’Connor’s self-advancement advanced the movement,” Hirshman writes,[23] and that much is true. But that also may be the gist of it. O’Connor was more progressive on women’s issues than on the myriad of other issues she considered, and she was more progressive than fellow Reagan appointees Scalia and Kennedy across the board. Yet at the end of the day, it’s hard to say that O’Connor’s votes were good for the women’s movement. What she brought to the bench as a woman was not nearly as influential as her allegiance to the establishment that put her there.

Ginsburg’s views, by contrast, were a threat to the establishment. She thought the social order needed changing and that’s what she set out to do—first as a law professor, then as a litigator with the ACLU. On women’s issues, Ginsburg was a sure bet, having committed to the project of gender equality from the start. But her appointment in 1993 came much later, over a decade after O’Connor’s appointment and three decades after the women’s movement began.

So which appointment did more for the movement—the symbolic first or the substantive second? My pick is Ginsburg, but when I posed the question at a dinner party recently, two of my colleagues went the other way. O’Connor paved the way for Ginsburg, they said, although others astutely pointed out that Ginsburg paved the way for O’Connor long before either appointment was made. In the end, Sisters in Law may not have fully explored the sorts of questions that a joint biography invites, but perhaps it did something better: it inspired conversations of their own.

That leaves just one more point from what I learned about being an elite, and it is the ugly truth: more daunting than the hurdle of gender is the power and privilege of class. I remember when O’Connor was appointed. I didn’t have dreams of being a Supreme Court Justice, but I remember thinking then that I could. From afar, I saw her appointment as a reflection of pure merit. Sisters in Law is a poignant reminder that class and clout mattered every bit as much.

In candor, there is a sting to this truth. The girl who grew up as the daughter of a mechanic (a darn good one at that) and joined the Army to pay for college wasn’t going to know people who know people. The ugly truth of the matter is that doors I assumed were open were probably shut all along. In the end, that’s what makes all that O’Connor and Ginsburg accomplished so important—when they went to the Supreme Court and changed the world, they changed it for us all.

Posted on 25 April 2016

CORINNA BARRETT LAIN is Professor of Law and Associate Dean of Faculty Development, University of Richmond School of Law.

[1] Linda Hirshman, Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World (2015).

[2] Id. at 21.

[3] Id. at 77.

[4] See id. at 21 (noting that none of the Justices, including the liberal William Brennan, was willing to hire a woman as a clerk in 1959); id. at 169 (“Even after five years on the tribunal, . . . Burger never assigned O’Connor to write the Court’s opinion in any big cases. As one of her clerks said sarcastically, remembering those years, ‘Oh, boy, another tax case! Thanks Justice Burger.’”); id. at 225 (discussing Blackmun’s resentment of O’Connor and his “wicked imitation of his female colleague’s distinctive loud, nasal diction”); id. at 227-29 (discussing Ginsburg’s comments on Blackmun’s draft opinion in J.E.B. v. Alabama and his response, which treated the astute comments as “an emotional event”).

[5] My own scholarship, for example, has typically been of this variety. See, e.g., Corinna Barrett Lain, Three Supreme Court “Failures” and a Story of Supreme Court Success, 69 Vand. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2016); Corinna Barrett Lain, God, Civic Virtue, and the American Way: Reconstructing Engel, 67 Stan. L. Rev. 479 (2015).

[6] Hirshman, supra note 1, at 251.

[7] Id. at 36.

[8] Id. at 37.

[9] Id. at 185.

[10] Id. at 190.

[11] The case, by the way, is Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357 (1978) (invalidating statutory scheme that made jury service optional for women).

[12] See Hirshman, supra note 1, at 61 (“…the perfect case for female self-determination, deliciously, a case of forced abortion”).

[13] See id. at 88 (“In a delicious irony…”); id. at 163 (“Deliciously, …”); id. at 227 (“…give a delicious glimpse”); id. at 231 (“Deliciously, …”).

[14] Id. at 136 (“…recalls her first clerk, Ruth McGregor. (MacGregor, in her late thirties, …”).

[15] Id. at 118.

[16] See Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896).

[17] Dahlia Lithwick, Yale, Harvard, Yale, Harvard, Yale, Harvard, Harvard, Harvard, Columbia: The Thing that Scares Me Most About the Supreme Court, The New Repub., Nov. 13, 2014, available at https://newrepublic.com/article/120173/2014-supreme-court-ivy-league-clan-disconnected-reality.

[18] Id.

[19] See, e.g., Hirshman, supra note 1, at 66 (“Right out of the box [Ginsburg] wrote to the president of Columbia, forwarding him the wonderful Rutgers affirmative action plan for getting more women on the faculty. In classic Ginsburg fashion, she starts the letter by reminding President McGill that they had already met at a parents’ night at the Dalton School.”).

[20] Id. at 66.

[21] Id. at 298.

[22] Hirshman, supra note 1, at 167-68 (discussing O’Connor’s vote in Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, 477 U.S. 567 (1986), limiting employer liability in sexual harassment claims); id. at 182-83 (discussing O’Connor’s vote in Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989), requiring that plaintiffs prove by direct evidence that sexism was a substantial motive for unfair treatment); id. at 190-94 (discussing O’Connor’s vote in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992), adopting the ‘undue burden’ test and holding that every provision of the state law burdening abortions was not an undue burden except the spousal notification requirement); id. at 246-47 (discussing O’Connor’s vote in Gebser v. Lago Vista Independent School District, 524 U.S. 274 (1998), refusing to hold school district liable for harassment of a student by a teacher); id. at 249 (discussing O’Connor’s vote in Miller v. Albright, 523 U.S. 420 (1998), upholding sex-based citizenship requirement regarding illegitimate foreign-born children).

[23] Id. at 50.