By BLAKEY VERMEULE

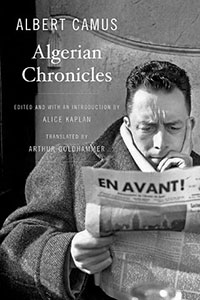

Review of ALGERIAN CHRONICLES, by Albert Camus; edited by Alice Kaplan and translated by Arthur Goldhammer

Belknap Press | Harvard University Press, 2014

View THE ENGAGED INTELLECTUAL .pdf

Albert Camus died in a car crash on January 4, 1960 when his friend and publisher Michel Gallimard ran his sports car off the road and smashed into a tree. Gallimard and Camus were driving back to Paris after spending the holidays in the south of France. This was a playboy’s death. Camus loved meeting new women (except for intellectual ones as Simone De Beauvoir discovered) (Bair 290). He had a full and rich extramarital love life. Before setting off for Paris, Camus sent letters to no less than three of his mistresses professing his desire and arranging to meet (Todd 411–412). The letters arrived and he did not. He was 46.

The end of a life, like the end of a story, casts a strong backwards pull on the earlier parts of it. If Camus had lived longer, he might have changed from a handsome charmer into a veined and bloated grotesque. Or, like Sartre, he might have become a museum of womanizing, the prisoner/director of an institution as labyrinthine in its rules, hierarchies, relative standings, backbiting, and jealousies as anything conceived of by the Roman Curia. (Sartre called his weekly schedule of girlfriend visits his “medical round.”) But Camus’s novelty-seeking passions for young (often actress) girlfriends left a deep open wound in his survivors, especially his wife Francine who had suffered depression for years because she felt rejected by him (Todd 349). His love life lingers on as part of his charismatic fatalistic aura. So too does the manner of his death. In a perfect irony, the great absurdist often told people that the most absurd way to die would be in a car crash. (A further deeper irony is that the death of an absurdist philosopher should have any meaning at all.)

The story that did not close, change, or undergo some ironic twist when Camus died was the story of his relationship to Algeria, his native country: “Algeria is the absent one, whose memory and abandonment pain the hearts of a few people.…”(Todd 362). Camus, the son of a poor French father and an illiterate Spanish mother, was a “pied noir,” or black foot (the term has obvious racist undertones but may come from the black boots worn by French soldiers). Camus’s parents had settled in Algeria, as many Europeans did throughout the late 19th- and early 20th- centuries, seeking work. Camus’s father was killed in the battle of the Marne when Camus was a baby and his mother, who was mostly deaf as well as mute, worked as a cleaner. Camus grew up in a tiny apartment in Algiers and spent his days running on the beach in the sun in a state of pubescent bliss. He played soccer but his professional career was cut short by tuberculosis. A kindly and sympathetic schoolteacher encouraged him to study and write. Camus went to university, wrote a thesis on Plotinus and Augustine, became a journalist for an Algerian newspaper, wrote some magnificent essays strongly criticizing the French colonial system for its effects on the destitute Kablye region, moved to Paris at the beginning of the Occupation, and fell in with the crowd around Sartre and De Beauvoir. Camus became an instant celebrity—he was charming, energetic, and just mysterious enough that the intellectuals assumed he was a resistance fighter (Bair 271). Life was heady. He may have been—to mix my eighteenth-century French classics—Candide venturing into a gilded cage with those corrupt and scheming aristocrats the Vicomte de Valmont and the Marquise de Merteuil, but the cage suited him well and he gave as good as he got. Though when he fell out with Sartre, as he inevitably did because both were touchy and Sartre didn’t like men, he felt the blow keenly.

Camus was living in Paris when Algeria’s war of independence broke out. One of the bloodiest of the many decolonization wars of the 1950’s and 1960’s, the Algerian war polarized opinion in France, although the left bank crowd were all resolutely pro-FLN (Front Liberation Nationale, the Algerian nationalist/independence party). Their support was personally dangerous: in 1961 Sartre and de Beauvoir had to go into hiding because they were threatened by right-wing militants. The OAS, a paramilitary organization, bombed Sartre’s apartment on the Rue de Bonaparte (Bair 487). In the minds of many French people, including Camus, Algeria was not a colony. It was France itself, or in any case a part of France—administered, if badly, through departéments and so on. A slogan at the time ran: "The Mediterranean divides France as the Seine divides Paris. "[1] Camus wrote and spoke at length about the war. His views are conditioned by his moment. He is especially concerned about his people, the European-descended French of Algeria. He clearly believes that Algeria will continue to be part of France. Yet the word most often used to describe his response is silence. Other people have used this word about him and he used it about himself. To the writer Moloud Ferroun he reported on his state of mind this way: “When two of our brothers are caught up in a merciless fight, it is criminal madness to root for one or the other. I prefer the virtues of silence, if I must choose between wisdom reduced to silence and yelling off my head madly. When words can dispose of someone’s life without remorse, being silent is not a negative attitude” (Todd 387).

In 1958 Camus published a collection of his writings on Algeria, Actuelles III: Chroniques algériennes—the title means, essentially, topical writings. It was met with resounding silence (Camus 1–2). Even with the evidence of the book before them, other writers accused Camus of staying silent.

Silence is the very last word of his book—the silence of a prophet who knows he is without honor in either of his two lands. The book’s last essays mount a complex proposal for a federated Algeria, like Switzerland, only with relatively more independence for Arabs and European whites (whom Camus called French). The proposal is drawn from a French-Algerian lawyer named Mark Lauriol. It develops a grid of proportional representation in the French assembly for Muslims, French-Algerians, and metropolitan French. Each group would vote on its interests and come together to debate the interests they have in common. The proposal sounds hopelessly utopian, naive, and starry-eyed: Camus is trying to wrestle beautiful forms of mutuality and shared-governance from something irretrievably broken and bloody. His last words sound bitter: “Objective observers may well feel skeptical that these… conditions can be met. The advent of considerable new human and economic resources in both France and Algeria justifies hopes for renewal, however. If so, then a solution like the one described above has a chance. Otherwise, Algeria will be lost, with terrible consequences for both the Arabs and the French. This is the last warning that can be given by a writer who for the past 20 years has been dedicated to the Algerian cause, before he lapses once again into silence”(184).

Alice Kaplan and Arthur Goldhammer have done the Anglophone world a great service in editing and translating this book. Camus writes some achingly beautiful sentences, including this image made deeply poignant by his tuberculosis: “Believe me when I tell you that Algeria is where I hurt at this moment, as others feel pain in their lungs” (73). He writes fiercely: “The gulf between metropolitan France and the French of Algeria has never been wider. To consider the metropole first, it is as if the long-overdue indictment of France’s policy of colonization has been extended to all the French living in Algeria. If you read certain newspapers, you get the impression that Algeria is a land of a million whip-wielding, cigar-chomping colonists driving around in Cadillacs.” (85). Arthur Goldhammer’s translations are so faithful, so attuned to the spirit of Camus and to the robust beauty of his prose, that I find myself wanting to email him to beg him to start translating all the other great works of French prose whose English counterparts clunk along on the family bookshelf. (Goldhammer translated Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st -Century).

From his writings about Kabyle in the 1930’s to several previously unpublished letters from the later 1950’s, we can see how Camus’s silence is really just a sort of shutting down (or shutting up). His silence evolves slowly and will eventually, because of his death, become permanent—the whole story rather than simply a part of it (as Alice Kaplan writes in her excellent, very helpful, and informative introduction). Rather than staging a cowardly withdrawal, Camus honorably refuses to engage. I say honorably because it seems clear that as the opinion-mongers grew louder and more certain, clarifying one's view of events inevitably meant falsifying some part of the conflict. Granted, Camus was silent partly because his friends didn’t have ears to hear or didn’t want to listen to what he had to say. Criticized by another writer for not speaking out, Camus said “But I have spoken! You read my Chroniques algériennes, and you saw how the leftist press strangled that book.”

The story of the Nobel Prize Press Conference is emotionally gripping. Camus gave a press conference in Stockholm in 1957 when he accepted the Nobel Prize in literature. The press conference grew very heated, with challenges from FLN supporters in the audience (privately Camus said that he wanted to “Fight the FLN.”) (Todd 417) Camus made a statement that has since become notorious—all because the reporter for Le Monde paraphrased it rather than quoting it directly. Camus said: “People are now planting bombs in the tramways of Algiers. My mother might be on one of those tramways. If that is justice, then I prefer my mother.” Misquoted and parodied as “Between justice and my mother, I choose my mother, ” the sentence became evidence that Camus cared only about his own people (Camus 216).

When in 1957 he met with de Gaulle, who was just about to come back into power after a decade out of politics, any hopes that Camus might have had from that quarter were harshly dismissed. From his biographer:

In his Carnets, Camus noted, ‘March 5th. Conversation with de Gaulle. As I spoke of the risk of trouble from the fury of Frenchmen of Algeria if the country was lost [de Gaulle said], ‘French fury? I’m sixty-seven years old and I’ve never seen a Frenchman try to kill another Frenchman, except myself.’ ” Camus told Francine [his wife] that he had asked de Gaulle about the future of the poor whites of Algeria, and the general replied, ‘They will demand huge indemnities,’ terrifying Camus with his cynicism. When Camus suggested giving French citizenship to all Algerians, de Gaulle replied, ‘Right, and we’ll have fifty niggers in the Chamber of Deputies’ (Todd 386–387).

Eventually de Gaulle signed a peace accord with the FLN in the Savoyard town of Evian in 1962, two years after Camus’s death. At the time he said that France could wash its hands of the Algerian problem forever (Horne 17).

That, of course, is the greatest irony of all. The story of French Algeria, of the French in Algeria, and especially of Algerians in France is still being written. The desire to make Camus speak to our current “situation” hovers around this volume—his writings, says Kaplan, have an “uncanny relevance” (Camus 6). As I read I found myself wondering: what do Camus’s occasional political writings from the 1930’s, 40’s, and 50’s have to say about French politics now or about the effects of colonialism or about the ongoing political unrest in north Africa?

I arrived in France exactly 24 hours before the Charlie Hebdo attacks. Saïd and Chérif Kouachi, who killed 12 people at the French satirical magazine before themselves being killed after a nine- hour hostage standoff in a suburban warehouse, were second-generation Algerians. Their parents died when the boys were still young. They grew up in grim suburbs, got into minor juvenile trouble, spent some time in prison, became radicalized and eventually joined the global jihad, affiliating with an organization called Al-Qaeda in Yemen. Almost immediately, the commentariat started talking about Algeria, the Algerian war, and the ongoing Algerian problem. As an outsider to the culture, I am not at all attuned to the many swirling sensitivities—there is much I just do not see (as for instance the possible racial undercurrents in the French response to the infamous Zinédine Zidane head butt at the end of the world cup finals in 2006) (Horne 2011, 17). But as I looked around for guidance and clarification—what sorts of passions do the Algerian war and its complicated aftermath—especially in Algeria—raise nowadays?-- I found that the loudest voices were the most certain and the most certain voices were the least informative. Everybody was trying to find an angle, to take a line, to drown out somebody else, to predict disastrous consequences, to moralize, punish, engage. And I found myself yearning for one or two intellectuals to be un peu désengagés—a bit less warlike and a bit more cautious. Maybe I was yearning for late Camus—a man who fell silent because he just didn’t know what to say.

Bair, Deirdre. 1991. Simone de Beauvoir: A Biography. 1st Touchstone Ed edition. New York: Touchstone.

Camus, Albert, and Alice Kaplan. 2013. Algerian Chronicles. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press.

Horne, Alistair. 2011. A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962. NYRB Classics.

Todd, Olivier, and Benjamin Ivry. 2011. Albert Camus: A Life. 1st American ed edition. Knopf.

[1] I am grateful to William Flesch for the reference.

BLAKEY VERMEULE is Professor of English at Stanford University.